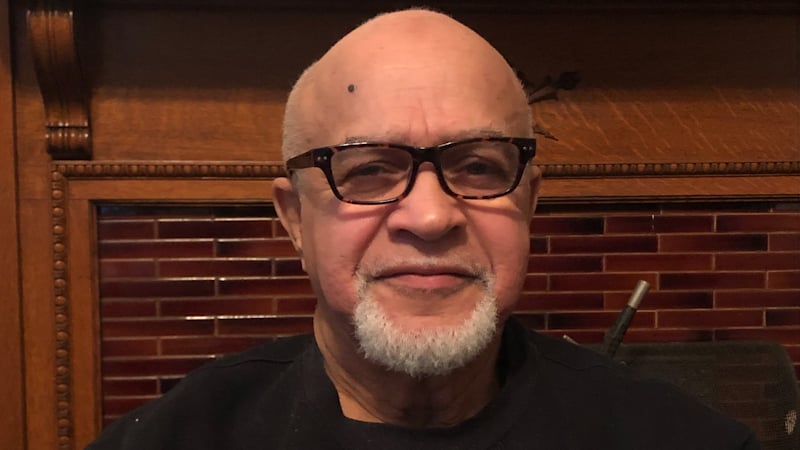

CEO Chris Coleman reflects on an unprecedented year and the path forward

As we turn the corner to start a new fiscal year at Twin Cities Habitat, I find it hard to remember what things were like before the pandemic began...

3 min read

Chris Coleman

:

10:30 AM on August 27, 2020

Chris Coleman

:

10:30 AM on August 27, 2020

I bought my first house when I was 24 years old. I had just finished my first year of law school and was still living at home. My mom, after raising six kids, was apparently ready to have an empty nest. I was two years away from actual job and had no money to speak of.

The Realtor, a shirt-tale relation, owned some rental properties. I asked if he had any openings. His reply caught me off guard. “Why don’t you just buy a house.” I shared with him the above – no job, no money. He said, “no problem.”

I did end up buying a house in Frogtown for the astronomical sum of $49,000. However, I needed a little help with the down payment. So, like many first-time homebuyers, I went to the tried and true First National Bank of Mom and she gave me the down payment. (I think she was really anxious to get rid of me.)

Thanks to "First National Bank of Mom," I could afford to buy my first house with no job and no savings. Photo above is captured via Google Street View 2014.

My mom grew up in deep poverty during the depression in the Rondo Neighborhood of St. Paul. My father grew up only slightly better off in Frogtown. As he once told me, “During the depression, we were all poor. But your mother grew up REALLY poor.” So how was my mom able to help, not just me, but my other siblings buy homes? The answer is simple.

She and my dad, most likely using the G.I. Bill, bought a house back in the early 1950s. As the family grew, they bought a bigger house. As it grew more, yet another. All along the way, they built equity. Because they had that first opportunity to buy a home, almost 35 years later, I was able to buy a home with her help.

Unfortunately, the opportunity that my parents had that gave me my opportunity did not exist for African American families and other families of color. Soldiers returning from fighting overseas received the benefits of the G.I. Bill – if they were White. But under “The Color of Law” (the title of Richard Rothstein’s vital work on purposeful discrimination), Black soldiers could not access the benefits to which they were entitled. Restrictive covenants meant homes could not be sold to non-whites. The banking industry's practice of redlining meant neighborhoods of color were marked "hazardous" for loans.

If an African American prevailed and ended up buying a home (often subject to usurious lending practices such as high-interest contract for deeds), cities, states, and the federal government built freeways through what they considered undesirable neighborhoods – giving the property owners pennies on the dollar.

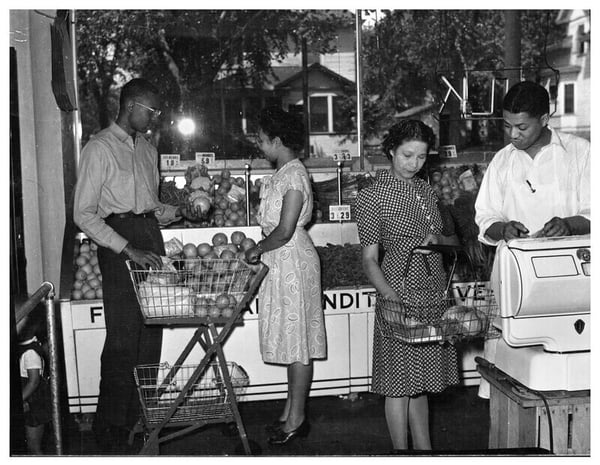

The Credjafawn Co-op Store, pictured above circa 1948, was a grocery store in the Rondo neighborhood in St. Paul. Rondo was a thriving Black neighborhood until the construction of I-94 tore the heart out of it. Read about Rondo and I-94 here. Photo used with permission from the Minnesota Historical Society.

The effects of those policies are as real today as they were almost three-quarters of a century ago. You can see it in the inequitable rates of homeownership. In Minnesota, 75% of White households own their homes compared to less than 25% of Black households. It plays out in disparities in net wealth: $171,000 for White families, $17,150 for Black families according to the Brookings Institute.

And, because we know how vital stable, safe, affordable housing is for a family’s overall well-being, it plays out in health, education, mobility, and so many other ways. We are paying the price for racist and intentional policies that kept families of color from building multi-generational wealth through homeownership.

So, the ability my mom had to help me buy that first home does not exist for far too many Black, Indigenous, and families of color.

I have often said, every dollar spent on affordable housing, from sheltering the homeless to affordable homeownership, is a dollar well spent. But affordable rental is palliative while affordable homeownership is curative.

We must not forget, in order for our society to become truly equitable, all families must have the same opportunities mine did. And Black moms should have the same opportunity to help their children that my mom had – even if it’s only to get her last child out of the house.

Your gift unlocks bright futures! Donate now to create, preserve, and promote affordable homeownership in the Twin Cities.

As we turn the corner to start a new fiscal year at Twin Cities Habitat, I find it hard to remember what things were like before the pandemic began...

Twin Cities Habitat has a core valueof Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...

Twin Cities Habitat has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...