Unequal Access to 'First National Bank of Mom'

I bought my first house when I was 24 years old. I had just finished my first year of law school and was still living at home. My mom, after raising...

3 min read

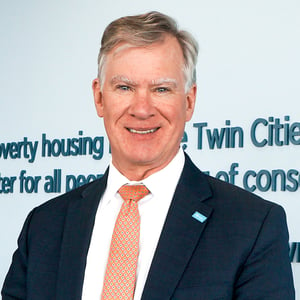

Chris Coleman

:

4:50 PM on June 5, 2019

Chris Coleman

:

4:50 PM on June 5, 2019

Twin Cities Habitat has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and cultural competency in all aspects of our organization.” We believe it’s important to learn from our national and local history of racist housing policies as we build for the future. This blog series explores the past, offers solutions for the future, and highlights ways you can take action.

This week marks my one-year anniversary as President and CEO of Twin Cities Habitat. In that time, I’ve learned a lot. I have learned how hard our incredible staff work to serve families throughout the community – be it our Homeownership Advisors helping families become homeowners, our Mortgage Foreclosure Prevention specialists keeping families in their homes, our A Brush with Kindness staff doing needed repairs for longtime homeowners, or Age in Place staff pioneering new ways to help our seniors. Through our Multiplying the Impact Campaign, we have doubled the number of families who partner with us. This year, we will help more than 110 families become first-time homeowners.

This week marks my one-year anniversary as President and CEO of Twin Cities Habitat. In that time, I’ve learned a lot. I have learned how hard our incredible staff work to serve families throughout the community – be it our Homeownership Advisors helping families become homeowners, our Mortgage Foreclosure Prevention specialists keeping families in their homes, our A Brush with Kindness staff doing needed repairs for longtime homeowners, or Age in Place staff pioneering new ways to help our seniors. Through our Multiplying the Impact Campaign, we have doubled the number of families who partner with us. This year, we will help more than 110 families become first-time homeowners.

One thing is clear: it was no accident.

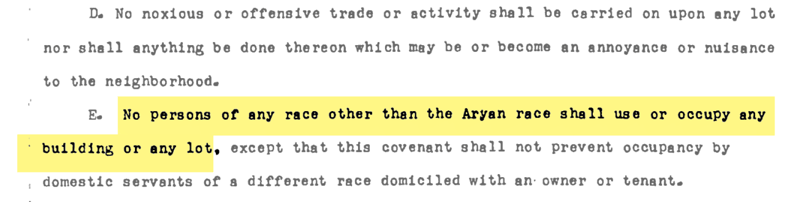

The Mapping Prejudice Project has unearthed unsettling discriminatory housing policies throughout the Twin Cities. So far, researchers and volunteers, scouring Hennepin County property deeds, have found well over 17,000 restrictive covenants that prevented people of color from purchasing homes in many Twin Cities neighborhoods. The language of these deeds shocks the conscience.

An example of a racially restrictive housing covenant from Hennepin County, from the Mapping Prejudice Project.

Over the last few months, Kirsten Delegard, Mapping Prejudice co-founder, presented to the Twin Cities Habitat’s Board of Directors, staff, and other groups, stimulating great conversation. The Mapping Prejudice team’s work was also featured in an eye-opening documentary from Twin Cities Public Television: Jim Crow of the North. It shows how racial covenants, redlining, and other policies conspired to create the racial segregation and disparities we see today in the Twin Cities. It recounts stories of firebombing and riots when black families moved into white neighborhoods. Every Minnesotan should see this documentary.

Many of us find our own stories tied up in this painful history.

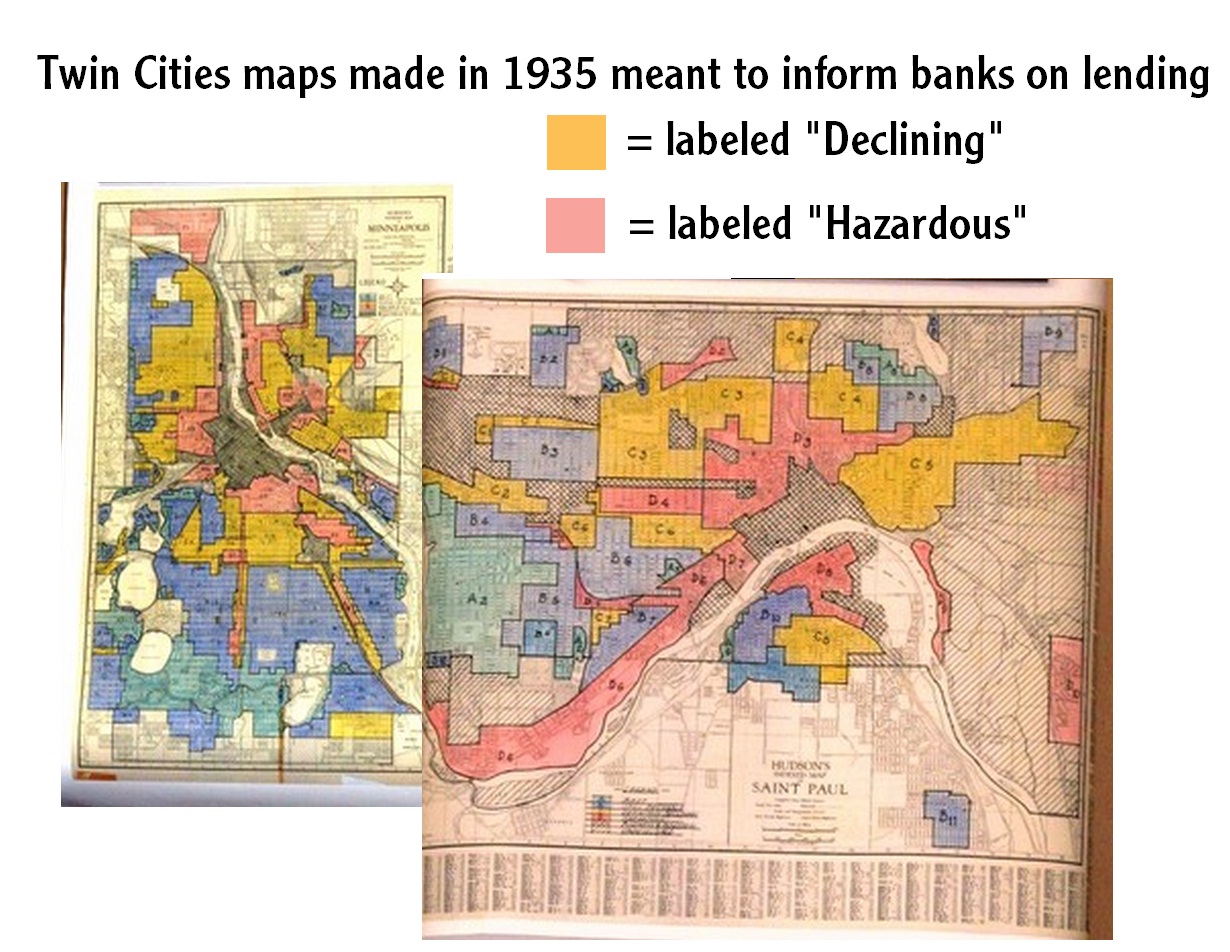

The largest expansion of homeownership in our country’s history occurred following WWII. Service members like my father came home from the war, went to college and bought a home with help from the GI Bill. However, because of banking practices known as redlining, black soldiers who had fought for their country – often alongside white soldiers – found they couldn’t live side-by-side their white comrades in America. They could not obtain a home loan in the communities to which the restrictive covenants relegated them.

Neighborhoods in the Twin Cities and around the country were labeled "Hazardous" if African Americans lived there, so the home loans offered there were much worse.

Other federal, state, and local policies added to the problem. As part of the New Deal, the Federal Government built new housing across America. But, as Richard Rothstein’s outlines in his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, these programs often created segregated neighborhoods from previously integrated communities. The Rondo neighborhood in Saint Paul is a prime example. While Rondo was considered the African American neighborhood, many white families (including my mother’s) lived there. White and black children went to school together. After WW II, it was one of the few neighborhoods where blacks could buy a house. But a few short years later, those homes were being cleared to make way for I-94. Families were given pennies on the dollar for their property.

The neighborhood never recovered and the scars from the forced dislocation from their homes still haunts many sons and daughters of Rondo. (I also highly recommend reading Voices of Rondo: Oral Histories of Saint Paul’s Historic Black Community.)

If we want to address today’s affordable housing crisis and the inequality we see throughout our community, we need to do more than just avoid the mistakes we made in the past. We need to be as intentional about closing the racial homeownership gap as we were about creating it.

For most of us, our homes are our biggest assets. The equity we build through homeownership is passed down from generation to generation. They’re our nest eggs for education, retirement, and our children’s futures. At Twin Cities Habitat, we are working hard to help rectify past wrongs. By helping families of color buy their first home, we start to undo past wrongs and help a new generation of Minnesotans share in this region’s prosperity.

Your gift unlocks bright futures! Donate now to create, preserve, and promote affordable homeownership in the Twin Cities.

I bought my first house when I was 24 years old. I had just finished my first year of law school and was still living at home. My mom, after raising...

Twin Cities Habitat has a core value of Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...

Twin Cities Habitat has a core valueof Equity and Inclusion which states: “We promote racial equity and strive to increase diversity, inclusion, and...